Why DAFs Pose Big Problems for Nonprofits and Social Progress

Request a Demo

Learn how top nonprofits use Classy to power their fundraising.

This piece was written by Classy Senior Data Scientist Robertson Wang.

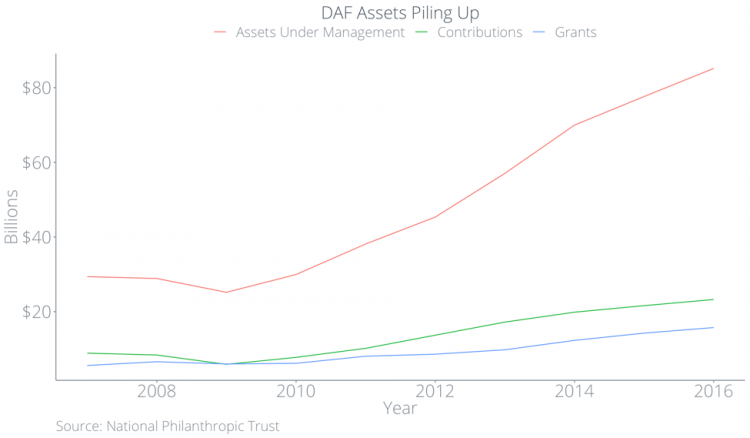

Donor advised funds (DAFs) are a type of brokerage account designed for charitable contributions that allow donors to give in a tax advantaged way. They have grown considerably in recent years in terms of total assets.

According to the National Philanthropic Trust, contributions to DAFs rose 15.6 percent per year on average from 2012 through 2015. In 2017, total assets in DAFs totaled $85.15 billion while donations from DAFs only totaled $15.75 billion. To put this in perspective: DAF assets are so large they represent twenty percent of 2017’s giving, yet donations from DAFs only represent four percent of 2017’s giving and less than twenty percent of DAF’s total ability to give.

Why the discrepancies? We conducted research to answer this question and to better understand not only why DAFs have seen such tremendous growth, but also what this means for nonprofits. Below, we’ll examine:

- The nature of DAFs in depth

- Their rise in recent years

- How assets in DAFs are “piling up”

- Who DAFs benefit

- How DAFs fit into a nonprofit’s larger strategy

What Exactly is a Donor Advised Fund?

Donor advised funds are an investment vehicle through which donors can optimize tax benefits from charitable donations. Donor advised funds allow donors to:

- Donate non-cash assets, such as shares in a private company or real estate

- Give more by avoiding capital gains taxes

- Claim tax benefits when they place assets into the DAF rather than when they actually give to a nonprofit organization

- Choose nonprofits to donate to at some undetermined moment in the future, without penalty or restriction

To further illustrate how DAFs work, I’ll offer an example. Imagine a donor that makes $100,000 a year and they have stock in a publicly traded company worth $10,000 that they bought for $0. Let’s also say that this donor is about to retire next year.

- If they put the stock into the DAF this year, they can receive a tax deduction of $10,000, thereby lowering their tax burden by $2,100 (assuming a 21 percent effective tax rate and no Schedule A limitations) as well as avoiding potential capital gains taxes of $1,500 (assuming a 15 percent long-term capital gains tax). Once contributed into the DAF, they can then transfer the stock to organizations in the future.

- If the donor had waited a year to put the stock into the DAF, they may receive zero tax deductions if they retired and no longer have taxable income.

- If the donor sold the stock and gave the proceeds to an organization, the donor would pay capital gains taxes of $1,500. The nonprofit organization would receive $8,500 and the donor receives an $8,500 tax deduction, thereby lowering their tax liability by $1,785.

On the face of this example, contributing the stock to the DAF is a win-win scenario: the taxpayer receives a near-term tax deduction and nonprofit organizations get more money because donors can avoid capital gains taxes and receive a larger tax benefit. Unfortunately, this doesn’t play out in reality. Next, we use public data to show how DAFs can pose significant challenges for organizations and how their rise could mean a sea-change for the nonprofit world.

The Rise of Donor Advised Funds

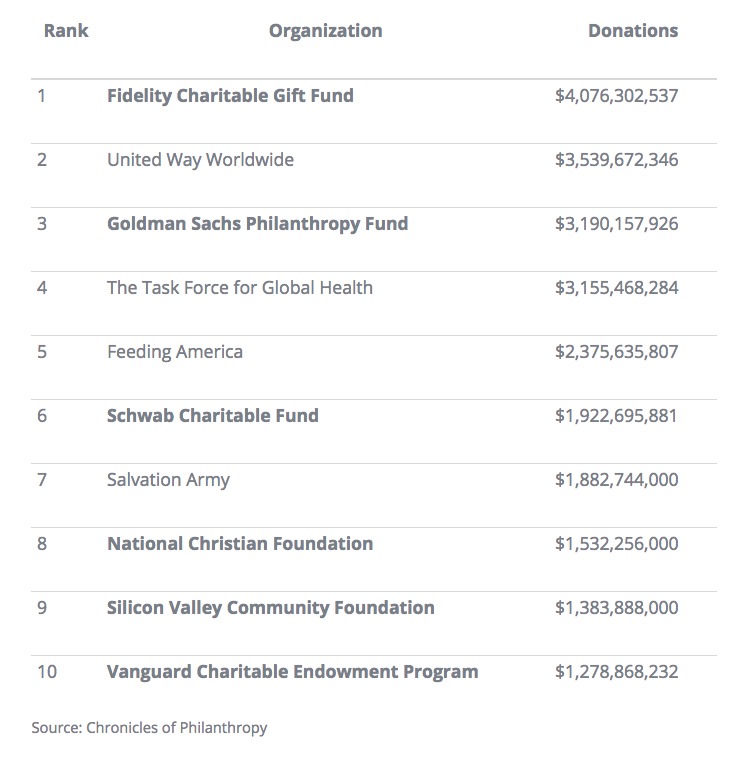

From 2015 to 2016, DAFs grew by 9.7 percent in terms of total assets. In 2016, Fidelity Charitable, a DAF manager, beat out United Way as the biggest “nonprofit organization” in the United States. According to the Chronicle of Philanthropy, six of the top ten nonprofit organizations in the United States were DAFs and four of the top ten were operated by financial institutions. The two non-financial DAF managers were the Silicon Valley Community Foundation and the National Christian Foundation.

DAFs haven’t always been so popular. The origins of DAFs can be traced to community foundations such as the New York Community Trust and the Jewish Community Federation of Cleveland. The Tax Reform Act of 1969 created a clear division between public charities and private foundations. Although not codified into law, early DAFs allowed organizations to straddle the line between being a public charity and managing money like a private foundation.

Eventually financial institutions lobbied the IRS to receive approval to operate DAFs. DAFs were formally recognized as a legal entity in 2006; since then, the number of DAFs has more than doubled.

All funds in DAFs managed by financial institutions get invested in that institution’s mutual funds, wherein the institution takes a cut. The more assets the financial institution manages, the more they can charge in annual fees. In fact, one financial institution generated $5.4 billion of revenue in 2015, up from and $1.9 billion in 2008—that’s 131 percent growth.

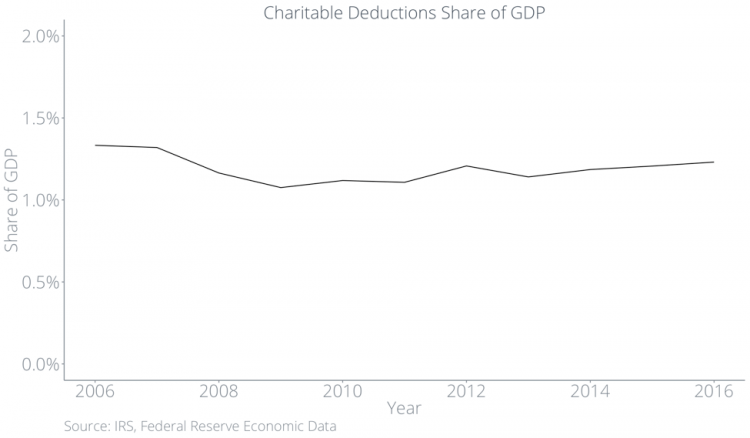

All the while, total charitable giving as a percentage of GDP has remained stagnant.

Charitable Giving is Piling Up Inside DAFs

From 2012 to 2017, total donation volume flowing into DAFs has been nearly two-thirds greater than total donation volume flowing out of DAFs.

Combined with the fact that overall giving, as a percentage of GDP, has barely changed over the past four decades suggests nonprofit organizations will receive less and less of the overall pie as DAFs continue to accrue and hold wealth.

The Impact on Traditional Methods of Giving

The biggest incentive for donors to give through DAFs is to get tax benefits. In order to receive that tax benefit, donors must claim their DAF contribution as a charitable deduction. Therefore, most of the money going into DAFs should show up as charitable deductions. If it were the case that DAFs increase overall charitable giving, then we would see an increase of charitable deductions as a percentage of GDP. We do not see this in the data.

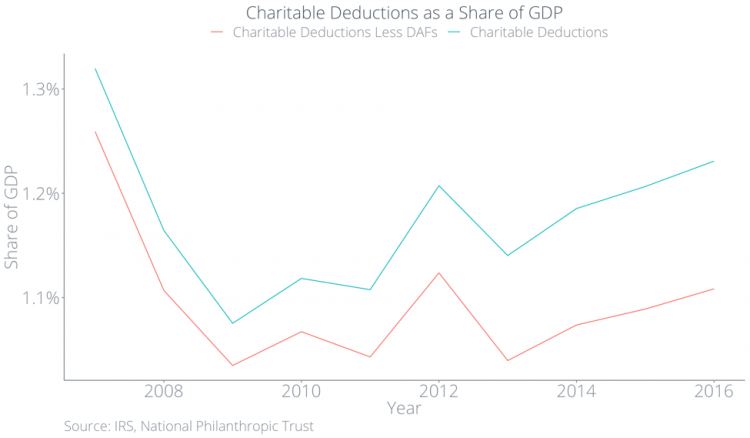

Below, we plot charitable deductions and charitable deductions less DAF contributions—both as a share of GDP. The blue line represents total charitable deductions, which is stagnant around 1.2 percent of GDP.

But DAF contributions are growing, so where are the funds coming from? The answer is that donors are likely substituting traditional forms of giving with giving via DAFs. In the below plot, the red line represents non-DAF giving, which has fallen below 1.1 percent of GDP, and the growing gap between the two lines represents DAF giving. In other words, people aren’t donating more because of DAFs, they’re just giving less in other ways.

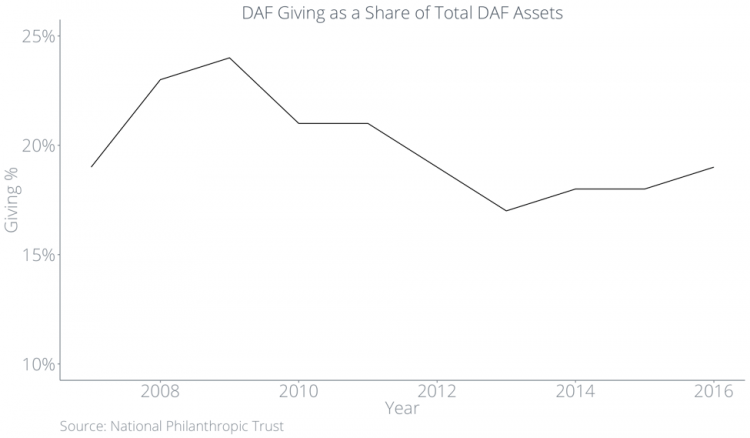

Donors claim a tax deduction when they place assets into a DAF, not when the DAF gives to an organization. Even though overall charitable giving hasn’t changed that much, the amount that DAFs are giving to organizations, as a percentage of assets sitting inside of DAFs, has been languishing below 20 percent in recent years.

In the most recent study on this topic completed by the IRS, they found that the median give rate was 7.2 percent in 2012 and that nearly 22 percent of DAFs made no donations at all.

All of this ultimately means that nonprofit organizations will have to wait for donations they would otherwise have received immediately while charitable giving languishes inside of DAFs.

A Closer Look at the Incentive Structure for DAF Managers

Why the piling up? The current tax incentive structures for donors and DAF managers encourages this behavior. DAFs are not required to donate money in any given year. DAFs are required to donate eventually to a qualified 501(c)(3) charity. However, donors can transfer their DAF assets to anyone they want, even after they pass away, so their donation may be at some impossibly distant point in the future.

Financial institutions have an incentive to keep money inside of DAFs instead of donating it to nonprofit organizations. So long as assets sit inside of a DAF, fund managers can collect investment fees and management fees. Based on a $10,000 initial donation, Fidelity Charitable collects $153.00 in annual fees plus investment fees regardless of how the economy is doing.

DAFs Benefit Some More Than Others

Not only are DAFs giving less and less, as a percentage of their total assets, their giving does not reflect traditional patterns of giving.

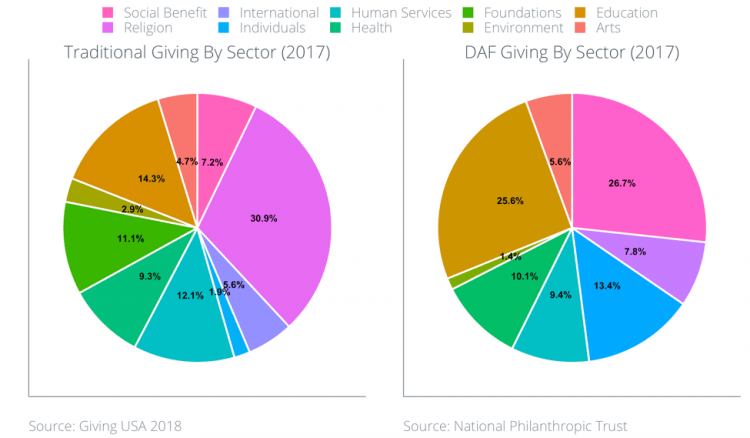

According to Giving USA, the five sectors that received the most charitable giving in 2017 were:

- Religion (31 percent)

- Education (14 percent)

- Human Services (12 percent)

- Foundations (11 percent)

- Health (9 percent)

Below is a plot of DAF giving, by sector, over the last three years. The biggest recipients of DAF giving in 2017 were the education (26 percent), social benefit (27 percent), and international (13 percent) sectors.

This clearly spells trouble for foundations and organizations in the religious and health sectors.

Most DAFs Stand Between Donors and Organizations

However, these sector breakdowns hide another potentially problematic fact: most DAF managers help select nonprofit organizations for their clients.

Fidelity Charitable makes recommendations to donors on which organizations to give to and Schwab Charitable provides investment advisors that also make recommendations to donors. In this way, most DAFs break the direct connection between donors and organizations by standing in the middle.

DAF managers’ recommendations align with giving to causes, not organizations. Eight-five percent of donors said they care about the effectiveness of the charities they support, but just three percent compared the relative performance of multiple organizations before making a donation. DAF managers identify organizations for donors which means that organizations could be compelled to spend time appealing directly to DAF managers to impact their behavior. The rise of DAFs means that organizations may shift their focus to appealing to a small group of DAF managers rather than focusing on spreading their message and mission directly to a large donor base.

By standing between donors and organizations, most DAFs make it harder for organizations to cultivate long-term relationships with donors. As DAFs can hide the identities of individual donors, it can be difficult for organizations to perform effective donor stewardship tactics and to share results directly with donors.

Online Fundraising Protects Stewardship Process

This inability to steward DAF donors is cause for concern for nonprofits. Without donor stewardship tactics, organizations are much less able to nurture one-time donors into becoming lifelong supporters that provide financial sustainability. It’s important for nonprofits to contrast the pros and cons of DAFs with more traditional means of giving to create a well-rounded overall fundraising strategy.

In contrast with DAFs, on traditional online donation platforms such as Classy, donations are directly channeled from donors to the organizations that they support. Platforms connect organizations with their donors so that organizations can directly spread their message to their supporters without a third party managing the process. Platforms democratize giving in the sense that they help organizations develop long term relationships with individuals rather than with funds and fund managers.

To address DAFs as nonprofits consider their overall strategy, nonprofits must play a part in communicating with their community and help donors understand the full ramifications.

What’s Ahead

Donor Advised Funds (DAFs) started as a relatively obscure tax vehicle that allowed community foundations to operate as public charities while maintaining funds like a private foundation. However, they evolved over time into a tax vehicle for individuals to optimize their charitable giving. DAFs are not required to make donations in any given year and DAF managers have an incentive to keep money in DAFs for as long as possible. Given that total charitable giving, as a percentage of GDP, has not gone up this means that organizations will continue to receive less of the overall pie.

Further, most DAFs stand between donors and organizations. As DAFs become an increasingly larger part of charitable giving, organizations may have to appeal to DAF managers rather than to donors. Nonprofits will potentially be compelled to focus their time and energy on a small group of funds rather than individual donors. In total, the rise of DAFs means long lasting changes in the nonprofit world.

Please note that Classy does not provide tax, legal, or accounting advice. This blog post is meant to explore the topic of donor advised funds and serve as a thought starter for nonprofit organizations.

The State of Modern Philanthropy

Subscribe to the Classy Blog

Get the latest fundraising tips, trends, and ideas in your inbox.

Thank you for subscribing

You signed up for emails from Classy

Request a Demo

Learn how top nonprofits use Classy to power their fundraising.

Explore Classy.org

Explore Classy.org